Designing Smart Glasses as a Assistive Technology

Our team explored what features and design considerations would make smart glasses an effective navigation solution for blind and low vision (BLV) users. The insights informed design implications for a user-centered smart glasses solution that supports real-time navigation and enhances independence.

**All Illustrations on this page have been created with AI (as the project was pre-design). Feel free to ask me how.

Overview

Project

People with BLV (blind or low vision) face two main problems outdoors: processing information like identifying objects and reading signs, and making decisions about safe routes and avoiding collisions.

As a pre-design project, my team set out to understand how smart glasses technology could address these navigation challenges, with the following research questions. By answering these questions, we could scope out design implications for a potential smart glasses solution:

How do BLV individuals currently navigate outdoor environments?

What specific challenges do existing assistive technologies fail to address?

What features would make smart glasses valuable for BLV navigation?

Role

My teammates and I collaborated on the interview questionnaire, interview data analysis, and literature review. I led the synthesis of research themes converting them into findings and design implications, and I also oversaw the writing and editing of the report.

Research Method

We conducted qualitative interviews as we needed deep insights into personal navigation experiences.

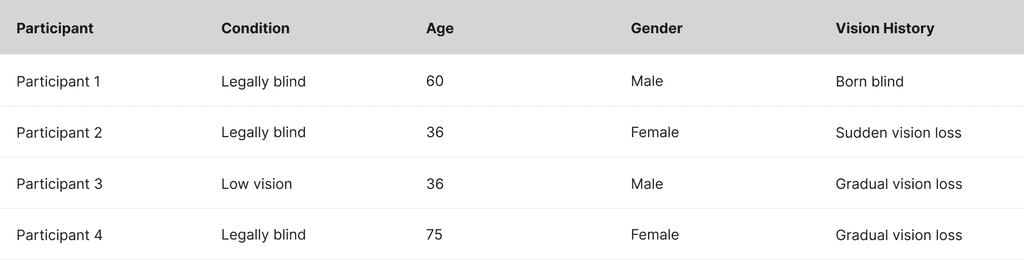

We recruited four participants through collaboration with Dr. Oliver Alonzo, ensuring representation of the blind and low vision (BLV) population. Virtual interviews accommodated participants across multiple cities.

FINDINGS

Navigation Strategies

We conducted evaluative research to test and refine our prototype design from mid-fidelity to high-fidelity through formative usability testing, A/B testing of visualization methods, and summative evaluation of the final product.

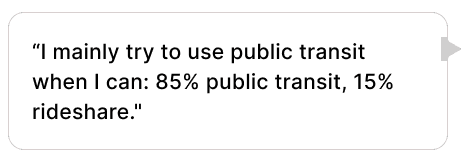

Navigation strategies reveal resource constraints

All participants rely on public transit, using buses and trains for most of their travel. They supplement with rideshare services only during bad weather or late hours due to cost constraints.

Participants plan their trips before leaving. They research routes, memorize building information, and pick departure times.

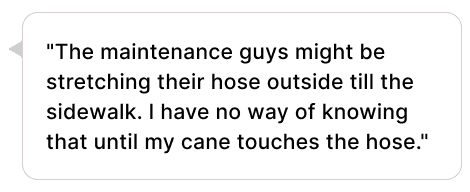

Environmental obstacles are hidden until contact

Participants cannot anticipate physical obstacles that appear between planned route and execution.

Such obstacles include uneven sidewalks, snow and ice, low-hanging signs, and construction barriers that traditional mobility aids cannot detect in advance.

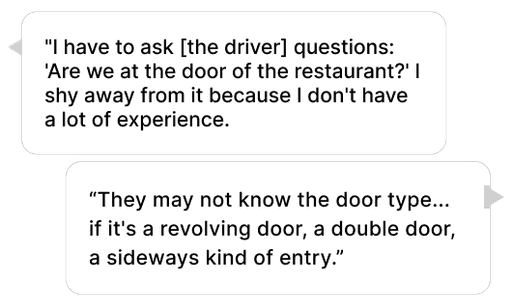

Finding locations and entrances

One participant with low vision stated that street signs are "almost impossible to see" and building numbers are "hard to read." Once participants reach buildings, most spoke of struggling with finding entrances:

FINDINGS

Current Technologies and Tools

We conducted evaluative research to test and refine our prototype design from mid-fidelity to high-fidelity through formative usability testing, A/B testing of visualization methods, and summative evaluation of the final product.

Overlapping apps overwhelm users

Participants use various specialized apps intended for those who are BLV, including BlindSquare, Microsoft Soundscape, and Lazarillo, but managing multiple audio streams becomes problematic. One participant noted: "Sometimes you can't run them all at the same time. Then you get too many voices in your head." Some favored apps like Nearby Explorer have become defunct over the years.

Multiple tools create friction

All participants carry canes when leaving home, and most juggle additional devices like their phone or in one case, a seeing eye dog. One participant described the challenge of carrying a cane: "It can get kind of heavy and tiresome after a while swinging it back and forth. It's hard to walk in a crowd or follow people using a cane.

Smart glasses are being used in an assistive way

One participant had used Ray-Ban Metas for six months and considered them valuable for identifying objects. However, they criticized the battery life requiring midday charging during work.

The same participant tried different smart frames but abandoned them due to appearance: "I felt like a target. They looked like high school chemistry goggles. I wore them for four days, and too many people commented."

FINDINGS

Perspectives on New Tools/Technologies

We conducted evaluative research to test and refine our prototype design from mid-fidelity to high-fidelity through formative usability testing, A/B testing of visualization methods, and summative evaluation of the final product.

Aesthetic acceptance determines adoption

Participants want assistive technology that helps them blend into environments without drawing attention. They described their canes as already "conspicuous" and preferred additional tools to be subtle. One participant appreciated using their smartphone for photos because it helped them "blend in."

AI comfort levels span the spectrum

Participants expressed varied comfort with artificial intelligence integration. One participant worried about accuracy: "I don't think it is accurate. I would rather have a human give real-life updates and rely on them more than AI." Two other participants expressed no concerns with AI implementation.

Costs affects all decisions

When shown Ray-Ban Meta pricing, two participants found the cost prohibitive. The participant who owns Meta frames acknowledged the value but recognized affordability barriers: "The price point was fair for the added assistance in their life but knew it could be unaffordable for others."

SyntHesis

Design Implications for a Smart Glasses Assistive Technology

The participants' experiences highlighted three key implications for smart glasses as an assistive solution: physical design requirements, technical performance specifications, and sustainability considerations.

Physical Design

Hands-Free Operation Is Non-Negotiable

Smart glasses solutions must provide voice user interface (VUI) for hands-free use. Participants already manage canes and service animals.Audio Feedback Must Preserve Environmental Awareness

Solutions must provide navigation audio while allowing users to hear sounds like traffic and transit announcements. Bone conduction technology is a promising approach.Aesthetics Determines Long-Term Use

Smart glasses must look like regular glasses to avoid stigma or highlighting disability.

Technical Performance

Real-Time Environmental Sensing

Solutions should detect head-level obstacles that canes cannot reach and provide advance warning of environmental hazards.Enhanced Entrance and Exit Identification

Smart glasses should identify building entrances, door types, and opening mechanisms.Unified Trip Planning Integration

Solutions should consolidate multiple app functions into a single interface with live weather and traffic information.

Sustainability and Value

Affordability > Adoption

Pricing must reflect the financial constraints of users. Solutions should provide significant value to justify investment.Customization Accommodates Diverse Needs

Features should include user-controlled settings for VoiceOver, augmented reality, and AI modes with easy opt-in/opt-out functionality. The wide range of participant vision levels and comfort with technology requires flexible solutions.Open-Source Development for Longevity

Solutions should leverage open-source development to prevent defunct applications like Nearby Explorer.

Future research

Next Steps

Were we to continue this project, we would begin by conducting a standard market review/competitive analysis of existing smart frames and their existing accessibility features. We also would explore the possibility of alternative interaction modes including gestures, touch, and haptic feedback.

If we moved into prototyping, we would user test high-fidelity prototypes for comfort and wearability across diverse environmental conditions (e.g., the rain and snowy streets). Lastly, we would look into potential integration with existing assistive technologies such as smart canes and low vision-focused apps.

Reflection

This was a meaningful project, as we were able to do research with blind and low vision individuals. While there are some existing accessibility guidelines for items like web interfaces, I learned that accessibility research for new products and technologies should be done ground-up, rather than rely on assumptions of principles from other interfaces or market technologies. Some things just cannot be transferred, and others just don't exist in a known canon, such as the consideration that BLV individuals are often holding a cane, their phone, and maybe a seeing eye dog, reducing their capacity for another handheld. Each interview was rich and loaded with insights, things I would have never considered. It highlighted to me how doing prototyping or even a survey without interviews kicking off the the process of designing assistive tech would have fallen flat.

If you have an opportunity in mind, or would like to chat, reach out at michellevpham@outlook.com. I'd love to hear from you.